The article below is by Dr. Oric Basirov. This orginally appeared in the CAIS (Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies) venue and was part of the CAIS series of lectures at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) on April 26, 2001.

The version printed below is different in that it has embedded photographs and captions used in Kaveh Farrokh”s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006.

![]()

Dr. Oric Basirov (left), Professor Emeritus of Iranian Studies David Bivar (center) and Shapour Suren-Pahlav host of the CAIS website (right) at SOAS 1998 (from CAIS website).

==================================================================

INTRODUCTION

As late as the closing decades of the 4th century B.C., the Iranian peoples were still the largest and the most widespread group within the great Indo-European family; this position must have been held for thousands of years by their nomadic ancestors, and was not relinquished until well into the Roman period; during those distant millennia, they roamed the vast, limitless Eurasian steppes as pastoralist riders and charioteers; towards the end of the second millennium B.C., some of them, lured by the great civilisations of the Indus vally, Elam, Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor, moved southwards and made permanent settlements; it didn’t take very long for one group of these settled people, the Medes, to form the first of the four Iranian empires, and less than 500 years for the Persians, to become the absolute masters of the known world; their nomadic ancestors, however, continued to roam the steppes, unopposed, for a very long time; it was not until the 5th century A.D. that the invading Turkic tribes pushed them out of their homelands into central Europe and further west; by then, of course, vast numbers of them had merged with eastern Europeans to form the core of the modern Slavs [1]; the rest were eventually assimilated in western Europe, especially in France; the intention of this paper is to give a broad outline of the history and the culture of these fascinating warriors, who for many thousands of years remained the indisputed masters of the steppes; throughout their long nomadic history, they are known to us by a variety of names, both native and foreign.

THE AIRYAS We owe a great deal to these pre-historical Iranians, one of whom, i.e, Zoroaster, is generally regarded as the first of the great prophets, and the earliest of the great thinkers; his people, in the holy texts, are referred to as Airyas, and their homeland, believed to have been somewhere in Eastern Iran, as Airyana vaejah; the word Ariya, noble, is also attested in the Inscriptions of Darius the Great and his son, Xerxes; it is used both as a linguistic and a racial designation. Darius refers to his Behistun inscription (DBiv.89) as (written) in Ariyan; he and Xerxes state in their surviving texts in Naqsh-i Rustam (DNa.14), Susa (DSe.13), and Persepolis (XPh.13): (adam) P~rsa, P~rsahy~ puça; Ariya, Ariya ciça; meaning: I am Persian, son of a Persian; an Aryan, belonging to the Aryan race.

![Beauty of Loulan]()

The Beauty of Loulan. A 3000-4,000 year-old mummy of a woman with red hair and Indo-European features found in the Tien Shan Mountains in northwest China. She was either a member of a proto-Iranian tribe or a proto-Celtic group that had migrated eastwards along with the proto-Iranians. The left photo is a reconstruction of how she would have appeared in life.

We meet this word again in Pahlavi literature, and in many Sasanian inscriptions, coins, seals and other documents; it is attested in Pahlavi as _r, meaning noble or hero; as Īrān, Iran; as Īrān-Shahr, meaning the Iranian Empire; as Īrān-vez, meaning the mythical original land of the Aryans; as an‘r, meaning non-Aryan, barbarian; and as anīrān, i.e., barbarity and ignobility. The earliest reference to this word in an Iranian context, however, predates Zoroaster and is attested in non-Gathic Avesta; it appears as airya, meaning noble; as airya dainhava (Yt.8.36, 52) meaning the land of the Aryans; and as airyana vaejah, the original land of the Aryans; this term, it seems, was adopted in remote antiquity by Iranians as their national identity [2]; hence other peoples were called Anairya, meaning non-Aryan, probably a derogatory racial designation like the other, more familiar, similar terms, such as, Greeks & barbarians, Jews & Goyim, Arabs & Ajams and Germans & Welsch.The fact that Iranians, Indians, and probably some Europeans also called themselves by this name, suggests that the word Airya may have been an old native designation for the racial group now called Indo-European, Indo-Germanic, European, Caucasian, or simply, White; it was indeed adopted in the middle of the 19th century as a collective designation for the above racial group and their languages.

THE SAKA

It seems that both nomadic and sedentary Iranians referred to themselves as Airyas; gradually, however, this word became a self-imposed designation for the settled Iranians only, who began to refer to their nomadic cousins in the East, i.e., Zoroaster’s people, as the Saka, and some of those further west as SKUDRA [[3]; the Saka probably did not call themselves exclusively by this name, some may have retained the use of the term Airya.

Many Saka tribes left the northern steppes intermittently to settle permanently in Central Asia, modern Afghanistan, and Persia; these tribes are the direct forebears of the imperial Western Iranians, the Medes, Persians and lastly, the Parthians.

![Boys of mazandaran]()

Boys from Mazandaran in Northern Iran. Iran has certainly been mutli-racial and multi-lingual since its inception at the time of the Medes and the Persians, with its distinct Indo-European character enduring to the present-day.

Once converted to Zoroastrianism, however, such became their religious significance, that by the middle of the 1st millennium B.C., the centre of the faith was neither in the homeland of its founder, nor in any of the adjoining Eastern Iranian regions; it was firmly established on the western side of the great salt desert, amongst the people now called Western Iranians; from then onwards, Eastern Iran fades into the background; we now deal almost exclusively with Western Iran, and until very recently, were not even aware of the fact that Eastern Iran had played such a vital part in the genesis of the Iranian empires, and their great national faith; most scientific facts, such as, the recorded history and Near Eastern archaeological data, especially a large volume of deciphered inscriptions, relate to the four great Western Iranian empires of the Medes, Persians, Parthians & Sasanians; there is only a small volume of classical sources, and more recent archaeological data, which also deal with the nomadic Iranians of the northeast, i.e., those Saka warriors who remained in the steppes, and were never completely subdued by the settled Iranians of the imperial period; these warriors remained, nonetheless, a very formidable enemy of their settled cousins; not only did they conquer and rule the Median Empire for 28 years in the 7th century B.C., but they also defeated and killed Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenian Empire, in the following century; a generation later, they were still engaging Darius the Great in many hard-fought battles; two hundred and fifty years later, however, they became the saviours of the Iranian culture and religion, and political integrity; they gradually pushed the Macedonians out of the Iranian homeland, and formed the Parthian Empire, which lasted for another 500 years.

The nomadic Iranians of the north western steppes, however, especially those settled in Europe, are extensively covered by the classical writers; they are also attested in a very large number of archaeological excavations in Eastern Europe; these Iranian peoples are known in the West as Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, and finally Ossets; it must be emphasised that all these names refer to the successive migratory waves of the same people, who probably called themselves by a name derived from the word Airya, as the Alans did, and the Ossets still do.

CIMMERIANS

The earliest recorded nomadic western Iranians are the Cimmerians; they make their first appearance in Assyrian annals at the beginning of the 8th century B.C., where they are referred to as Gimmiri; they came down from modern Ukraine, and conquered eastern Thrace, and most of modern Turkey, being pushed westwards by another nomadic Iranian people, the Scythians (see below); they left behind a wealth of archaeological material, including a vast number of mound-burials in western Asia Minor; they later allied themselves with the Medes against the Assyrian Empire; the word GIMMIRI is attested in the Old Testament (Genesis I.x.12), as GOMER, the name given to one of Japhet’s sons (see below, Scythian/Ashkenaz [4]).

SCYTHIANS

This is by far the most important, and enduring designation given by the classical sources to the nomadic Iranians of the steppes; the name refers to the entire non-sedentary Iranians, both in the West, and in the East (the Saka). Greek records place them in southern Russia in the 8th century B.C., however, recent archaeological evidence testifies that they, Cimmerians, and other Steppe Iranians may have been there far earlier. Greek geographers of the 4th century B.C. also credit the Scythians with inhabiting the largest part of the known world (map Red 16).

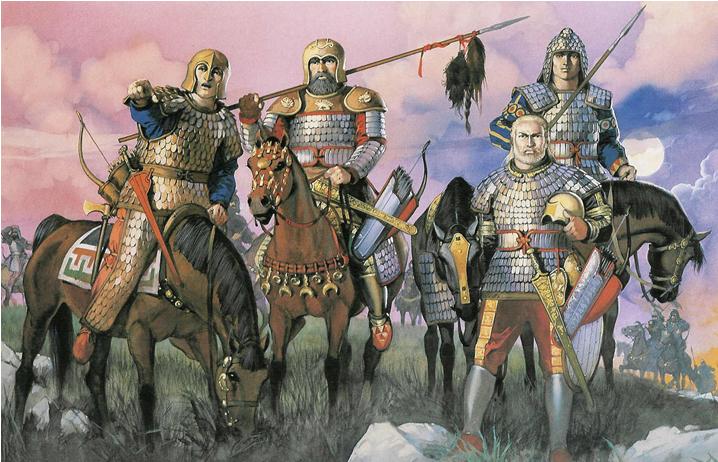

![Scythians in ancient Ukraine]()

Scythians on the steppes of the ancient Uklraine. Scholars are virtually unanimous that the Scythians were an Iranian people related to the Medes and Persians of ancient iran or Persia. Painting by Angus McBride.

Like other Iranians, these nomads probably called themselves by the generic term “Airya”; this is testified inter alia by the native name of their descendants in the present day Europe (see below); it seems, however, that they, or at least some of their powerful clans, also called themselves “SAKA” in the East, and *SKUنA, SKUDA, or SKUDRA [5] in the West. SKUDA is believed to be related to the German word “SACHS”, meaning a type of throwing-dagger which the eponymic Saxons used to carry and shoot with[6]; indeed, it is possible that like the historical Saxons, the Skuda derived their name from their ability to shoot. [cf. Franks]. Their first appearance in recorded history is again in the Assyrian annals, where they chase the Cimmerians, their own kinsmen, first out of Europe, then out of Asia Minor into the Median territory; in the 7th century B.C. they allied themselves with the Assyrians, and attacked the combined forces of the invading rebellious Median vassal king, Khshathrita (Phraortes in Greek, Kashtariti in Akkadian) and his Cimmerians allies; the Assyrians repelled the Medes, killing Phraortes, and routed the Cimmerians; the real victors, however, were the Scythians; for the next 28 years, now allied with their erstwhile enemy, the Cimmerians, they ravaged most of the Ancient Near East, including Media; later they allied themselves with Khshathrita’s son, the Median emperor, Hvakhshathara II (Cyaxares in Greek, Uaksatar II in Akkadian), and the Babylonian king, Nabopolassar, taking Nineveh in 612 B.C. and destroying once and for all the mighty Assyrian Empire. (beginning of the Kurdish calendar)

The Scythians were called by the Assyrians Ashkuza or Ishkuza (A/Iڑ-k/gu-za-ai); as with the Gimmiri, this word also appears to have found its way into the Old Testament; one of Gomer’s (Gimmiri) three sons, in Genesis I.x.12, is called Ashkenaz, which has given us the modern Hebrew word, Ashkenazi[7].

The Scythians were known by the Achaemenians, as SAKA and SKUDRA, by the Greeks, SKغTHIA (سê?èéل), by the Romans, SCYTHIAE (pron. SKITYAI), which has given us the English word SCYTHIAN; they lived in a wide area stretching from the south and west of the River Danube to the eastern and northeastern edges of the Taklamakan Desert in China; this vast territory includes now parts of Central Europe, the eastern half of the Balkans, the Ukraine, northern Caucasus, southern Russia, southern Siberia, Central Asia and western China.

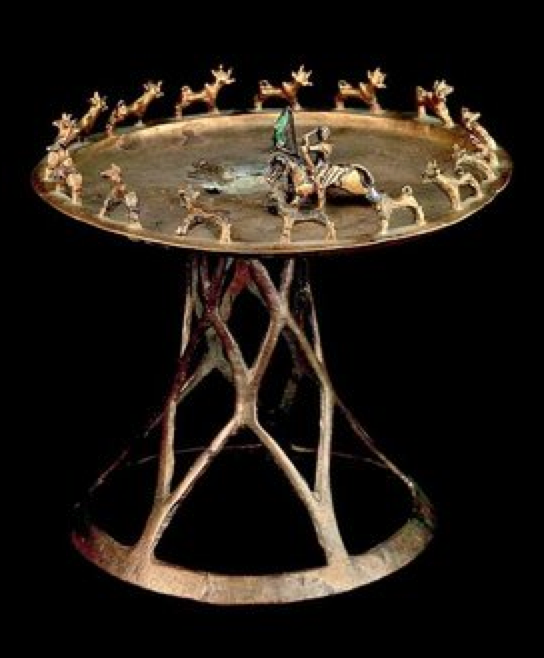

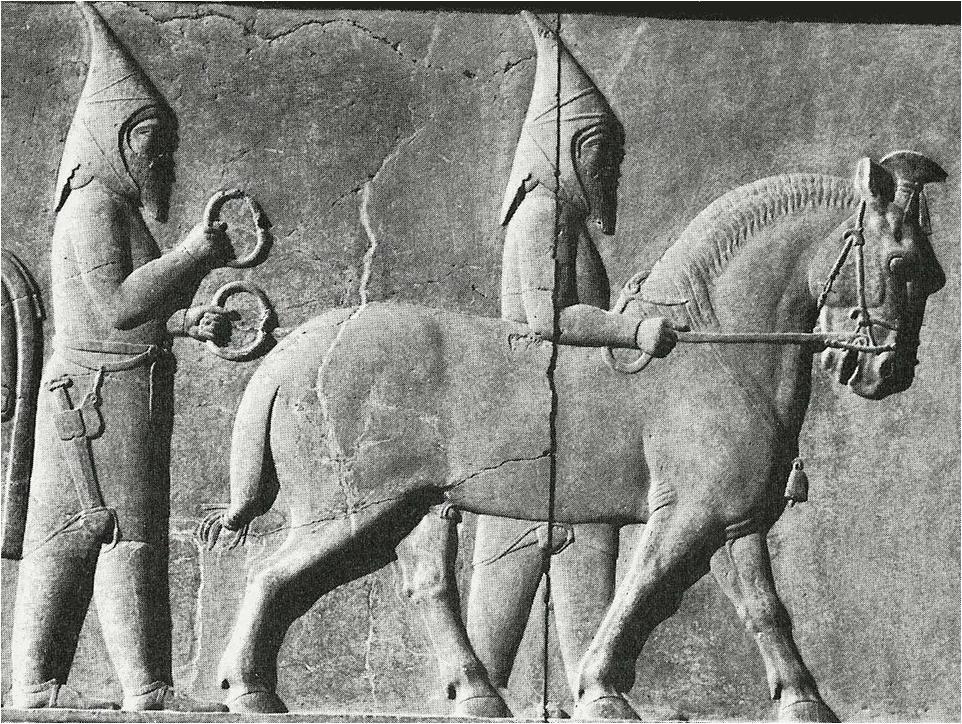

![The Sakas at Persepolis]()

Eastern Scythians or “Saka Tigrakhauda” (Pointed cap Saka) as depicted in Persepolis. The Scythians played an important role in the military machine of the Achaemenids. A branch of the Scythians or Saka, the Parthians, were to revive the Iranian kingdom after Alexander’s conquests and his Seleucid successors.

We know a great deal about their physical appearance; they were long-headed giants with blond hair and blue eyes; this well-known fact is attested by various classical sources [8], and by their skeletal and other remains in numerous archaeological excavations, which give a fairly detailed description of these ancient Iranians [9]; recently, a large number of their mummified corpses were discovered in western China; these mummies, which are extremely well-preserved in the arid conditions of the Taklamakan desert, are now on display at the museums of khotan, Urumchi, and Turfan in Sinkiang; they are dressed in Scythian costume, i.e., leather tunic and trousers, and are usually displayed in the sitting position, exactly as described by Herodotus; what is extra ordinary apart from their northern European features, however, is their gigantic heights, well over two metres as they are now, in spite of the natural shrinkage expected during the past thousands of years.

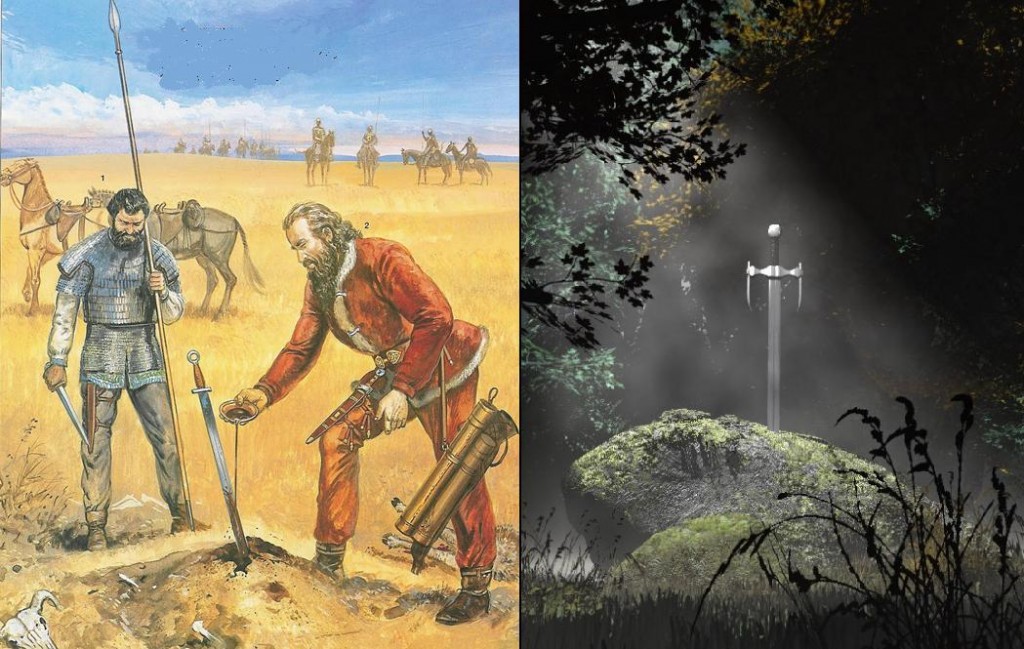

The Scythians, and other early steppe Iranians are believed to have been the first Indo-Europeans to use domesticated horses for riding (as opposed to eating); this theory has acquired fresh credibility after the recent discovery of horse skeletons at the Sredny Stog archaeological culture, east of the River Dniepr, a well-known pre-historical Scythian site in eastern Ukraine; these bones were identified as belonging to bitted, therefore, ridden horses dating to 4000 B.C., at least 2500 years older than the previously known examples.

More recent excavations east of the Ural Mountains credit them also with the invention of the first two-wheeled chariot [10]; such mobility, naturally, turned them into a formidable fighting force; they never willingly fought on foot, and used armour both for themselves and their mounts; they also developed the famous steppe tactic of faked retreat, and the “Parthian shot”, shooting backwards while on mounted retreat; this tactic, named after their well-known descendants, the Parthians, requires an amazing skill and balance in the saddle, and a dazzling co-ordination of eyes, arms and breath without the support of stirrups.

In this unique pastoralist equestrian warrior society, women fought alongside their men; not only they were held in an equal status with men, but also periodically they actually ruled them.

![Scythian Fenale Commander]()

Scythian female warrior accompanied by two of her male comrades. The tradition of female warriors was highly prominent in pre-Islamic and post-Islamic Iran. Painting by Angus McBride.

This so called upside-down society both fascinated and horrified the male dominated Greek culture; later, the Romans expressed the same horror, when they encountered the Celtic and Germanic female warriors. Greek writers called the fighting Iranian women they met in the Ukrainian steppes, the Amazons; later Greek sources placed them further east, in northeastern parts of Iran.

This incredible social equality, at such an early age, is irrefutably attested, not only by a host of classical writers, but also by a wealth of archaeological evidence; in many mound- burials in the former Soviet Union, it is by no means unusual to find remains of women warriors dressed in full armour, lying on a war chariot, surrounded by their weaponry, and significantly, accompanied by a host of male subordinates specially sacrificed in their honour; nonetheless, these young Iranian warriors, as evidenced by the archaeological remains of their costumes and jewellery, do not seem to have lost their femininity; they remained “feminine as well as female” as a great contemporary German scholar puts it [11].

![Sohrab and Gordafarid]()

Persian miniature depicting female warrior Gordafarid locked in a duel with Sohrab, the son of the ancient Iranian hero, Rustam.

Archaeological excavations also testify to the amazing skill of these people in making jewellery; some of the finds are so dazzling in quality and advanced in technique that it is hard to imagine that they are produced by an unsettled, nomadic culture; we are indeed very fortunate that these early steppe Iranians practised elaborate funerary rituals and interred their treasures with their dead in huge impregnable burial mounds; hence, the vast majority of the steppe Iranians’ artifacts known to the learned world is attributed to the Scythians.

As it has been emphasised throughout this paper these two names probably refer to the same people, who, in all likelihood, called themselves by a name similar to the word Alan.

Herodotus, who has devoted most of his Book IV to Scythians, is the earliest source on Sarmatians, whom he refers to as a branch of the Scythians; by the 3rd century B.C., the Sarmatians (Greek SARMATAI [سلٌىلôله]), had replaced Scythians in Europe, and settled in western Ukraine, the Danube Valley and Thrace.

The earliest known reference to the Alans (Greek ALANOI, Latin ALANI), however, is not until the mid 1st century A.D [12]; it appears that by then the Alans, in turn, had taken the place of the Sarmatians in Eastern Europe; both these Iranian peoples are frequently mentioned in Greek, Roman, and Byzantine sources as late as the middle of the fifth century A.D.

Alans, with an identical etymological origin with the word Iran, are extensively covered, especially by Ammianus Marcellinus who states inter alia, that “Almost all of the Alans are tall and good looking, their hair is generally blond” (AM, XXX,2,21); they once ruled a vast territory stretching from the Caucasus to the Danube, but were gradually driven westwards by the invading Huns; however, unlike their predecessors the Cimmerians, Scythians and the Sarmatians, the Alans did not vanish from the history; indeed they settled in the Byzantine Empire and Western Europe, playing a vital role in the subsequent European affairs; nonetheless, one finds it very odd that they are not given the full credit they truly deserve for being an important force in medieval Europe.

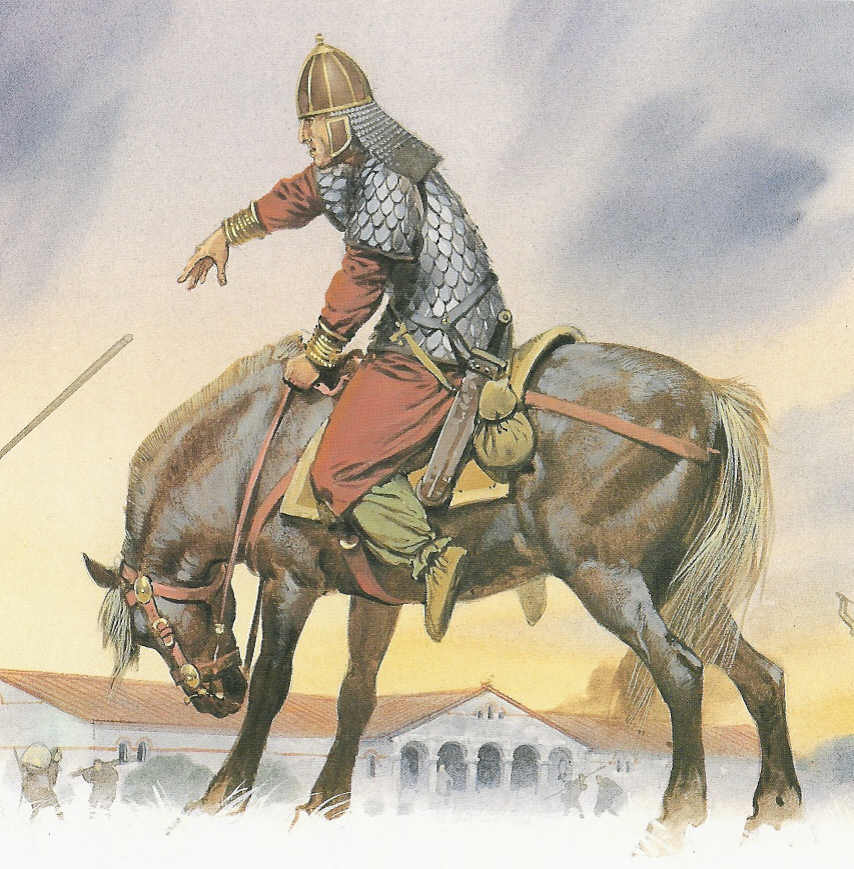

![Alan-Warrior]()

Iranian-speaking Alan warrior circa 5th century AD. The descedants of the Alans are found in the Caucasus as well as in the old Iranian province of Ard-Alan (Royal House of Alan) in western Iran. The legends of the Alans are recalled in the Kurdish folklore epic “Memi-Alan o Zhin e Bohtan”. Painting by Angus McBride.

Rostovtzeff, the great Russian expert in Iranians of the steppes, once complained that “In most of the work on the period of migrations, the part played by the Sarmatians and especially by the Alans in conquest of Europe is almost ignored; but we must never forget that the Alans long resided in Gaul, that they invaded Italy, and that they came with the Vandals to Spain and conquered North Africa” [13]; one can easily sympathise with the frustration of the great Russian scholar; unlike various German tribes and Slavs and hoards of Huns, Avars, Magyars and Bulgars, who dominate the historical literature dealing with the early Middle Ages, the Alans hardly receive a mention; yet, they were in fact the only non-Germanic people of the migration period to make important settlements in Western Europe, and for many years dominated the affairs of the late Roman Empire.

In 421, soon after their arrival in Constantinople, the Alan general, Ardaburius (Ardapur), fighting for the Byzantine emperor Theodosius, defeated the army of the Sasanian Emperor, Bahram V (Gمr), and took the fortified frontier city of Nisibus; after several more victorious campaigns in Italy he was made consul for the year 427; his son, Asp~r (aspwar, Saw~r), in 431 commanded a large army against Vandals and Alans in Africa, and was made consul for the year 434. Asp~r’s son, Ardaburius (named after his grandfather) was also made consul in 447; in 450 when the emperor Theodosius II died, Asp~r was offered the imperial throne by the senate of Constantinople; he declined the throne, but gave it to his subordinate, Marcian.

In 451 Attila the Hun laid siege to Orleans the capital city of the Alans in central Gaul; their new king, with the remarkably Modern Persian name of Sangiban, successfully defended the city, and with the help of his Roman and Visigoth allies pushed Attila to Chalons in eastern France; in the famous battle of Chalons Western Europe was saved from the ravage of the Huns.

![Alan at Orleans 451 AD]()

Alan warrior in combat at Orleans (circa 451 AD). Many of these Iranian speakers settled in what is now modern France and assimilated into the local population. To this day their legacy resonates in Eastern Europe with names such as Alan, Alana, Irene, and Rita. The Alans are now believed to have introduced much of their folklore into the Arthurian legends of the British Isles. Painting by Angus McBride.

From the mid fifth century A.D. onwards, Alans, now fully Christianised, gradually lost their Iranian language, and were eventually absorbed into the population of medieval Europe; as late as 575 one still comes across Iranian names, such as Gersasp in southern France, and Aspidius (Aspapati, Asppat) in northern Spain, and of course the word Alan itself, which is still a very popular name in western Europe[14].

Alans are credited for importing into western Europe their steppe tactics of warfare; these include never fighting on foot out of choice, having armour both for men and their mounts, and most significantly, the practice of tactical fake retreat; these Iranian steppe tactics were passed on to the Bretons, Visigoths and later, to the Normans, who used the fake retreat at many battles including the Battle of Hastings[15].

Alans are also credited with teaching western Europeans the still popular sport of hunting on horseback with hunting dogs [16]; a famous breed of medieval hunting dogs was called Alan (med. Latin Alanus) which, according to a 19th century authority on the history and origin of canine breeds, “derived originally from the Caucasus, whence it accompanied the fierce, fairhaired, and warlike Alani” [17]; the town of Alano in Spain to this day bears two Alan dogs on its coat of arms.

OSSETS

Fortunately for us, the Huns could not push all the Alans out of their homeland; their descendants, known as Ossets, are the only Iranians who still live in Europe; they call their country “Iron”, which is a variation of Alan, Iran, as well as Eran. Eran was the name of the Iranian Transcaucasia before it was lost to the Russians in the 19th century and subsequently renamed Azarbaijan.

Ossets are mostly Christian, speaking Ossetic, or as they themselves call it “Ironig”, or “Ironski”, which is classified as an Eastern Iranian language. Ossetic maintains on the one hand, some remarkable features of the Gathic Avestan, and possesses on the other, a number of words, such as, thau (tauen, to thaw, as in snow) and gau (region, district) which are remarkably similar to their modern Germanic equivalents.

![Palm Sunday in South Ossetia]()

Palm Sunday proecession in South Ossetia. The South Ossetians in Georgia are Christians while the North Ossetians in Russia are a mix of Muslims and Christians.

This modern Iranian nation, still provides a physical link between the Indo-Europeans of the East, and those of the West, that is, most people of Europe; such a romantic link, it will be remembered, had already been established thousands of years ago by their blond and blue-eyed ancestors.

![]()

Talysh girls from the Republic of Azarbaijan (ancient Arran or Albania) engaged in the Nowruz celebrations of March 21. The Talysh speak an Iranian language akin to those that were spoken throughout Iranian Azarbaijan unitl the Turkic arrivals of the 11th century AD.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Harmatta, J., “History of Sarmatians”, Budapest (1950), p.3.[2] Iranians are credited with being probably the first people to recognise the concept of nationhood, and to assume a proper national identity, which incredibly, has survived until the present day as Iran.

[3] e.g., DSe29, Kent, R., “Old Persian”, New Haven (1953), p.141.

[4] Gardiner-Garden, J.R., “Ktesias on Early Central Asian History and Ethnography”, Bloomington (1987), p.9-10.

[5] Szemerényi, O., “Four Old Iranian Ethnic Names: SCYTHIAN – SKUDRA – SOGDIAN – SAKA”, Vienna (1980).

[6] There is also a wealth of familiar names in many different languages which owe their origins to the word SKUDA; well known amongst them are USKUDAR in Istanbul, SOGDIA in Central Asia, and SAKAVAND and SISTAN in modern Iran; see Zsemerényi, op. cit.

[7] Believed to have resulted from a misreading of an original Hebrew “waw” as a “nun”; see n.4 above; it is noteworthy that the other Jewish racial designation, Saphardic, has also a strong Iranian association; it derives from the Lydio/Persian word Spherda/Sparda, i.e., the Greek Sardis.

[8] e.g., Ammianus Marcellinus, XXX.2.21.

[9] Mair, V.H., “Mummies of the Tarim Basin”, “Archaeology” vol.48, no.2, Mar & Apr 1995, pp.28-35.

[10] Anthony, D.W., & Vinogradov, N.B., “Birth of the Chariot”, “Archaeology” op. cit., pp.36-41, esp. p.38. Litauer, M.A., & Grouwel, J.H., “The Origin of the True Chariot”, “Antiquity” vol.70, No.270, Dec. 1996, pp.934-939.

[11] Rolle, Renate, “The world of the Scythians”, London NY (1989).

[12] Seneca, Thyestes.

[13] Rostovtzeff, M.I., “Iranians and Greeks in South Russia”, Oxford (1922), p.237.

[14] Bachrach, B.S., “A History of the Alans in the West”, UMP (1973), pp. 92, 102,107.

[15] op. cit., pp.88-91.

[16] op. cit., pp.118-119.

[17] Jesse, G.R., “Researches into the History of the British Dogs” II, (London 1886), pp.80-84, 116-118.